What are the factors needed to make art? or, more importantly, good art?

First, we need talent. Fortunately, talent is free, and we will always have a sufficient supply as long as there are new people. However, aptitude alone is not enough to create serious art work.

Second, there is skill. This is arguably at least as important as talent, but is decidedly not free. Some people develop a lot of skill on their own, while others choose school or apprenticeship. In either case, there are substantial personal sacrifices to be made: the energy to study and practice, the financial cost, and of course the next major factor…

Third, It takes massive amounts of time to do something right, and in the world of art, having the time to create something beyond the superficial can be a lifelong pursuit, blocking out many other activities that we, the Creative Class, find less important.

There are certainly other factors that may come into the equation, such as equipment, tools, supplies, instruments, and more, but in this day of mass-produced products, it’s pretty easy to get all the gear you need to get started. (unless you are doing large-format sculpture, diamond jewelry design or other expensive pursuits)

This brings us to the point: assuming talent is there, we need time and skill to create quality art; and what can we use to acquire these things? Money.

Who is Buying?

Today, essentially anything that can exist in digital form is now, by definition, available free. Any recording, photography, graphic design, software, literature that is not physically restricted to a tangible form is no longer of any value to the consumer at large. Why? Because people are inherently dishonest when deprived of shame or consequences. We will still buy food, cars, real estate, and other necessities, though small widgets will soon become like software once 3D printers are household items. (goodbye royalties on patented ideas)

As it stands, the prohibition against stealing physical objects is still a marginally enforceable law, though many thieves often do get away with robbery, because it’s easier to file an insurance claim than it is to recover the goods and prosecute the criminals. There are simply not enough police, and they are too busy raising revenue with traffic fines.

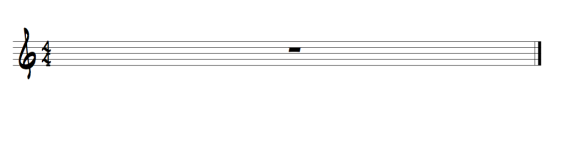

Likewise, since the value has been removed from the product, people no longer consider the skills of the artist to be of any value, either. As an example, auto-tune, loops and pre-packaged patterns created by others, rhythmic correction and other techniques have made the skills of singers and musicians difficult to market. And as time passes, the consumer has even less of an idea of what “real” music sounds like, and have no real experience in what true quality can be. Graphic design is now done by anyone with a computer, and most people can’t tell the difference between professional and laughably amateurish work. Terrible phone snapshots capture every moment of our lives, without need for photographers, and stealing an image is as easy as drag-and-drop.

Stop, Thief!

One might assume that well-established intellectual property law would at least have some moderating effect on this wholesale theft and give-away of the arts and other creative work. It is quite clear this isn’t working. China, the most populous nation in the world, has made a policy of piracy and the international community has been able to do little to fix it. Illegal file-sharing sites abound, instantly popping back up after being temporarily taken down. To show how ineffective law enforcement is on the internet, recall how it took years to finally find and prosecute the owner of the Silk Road drug site, despite the egregious nature of that business. Who has time for some lowly music or software pirates?

Worse yet, many young people, students and even fledgling creatives defend this wholesale devaluation of the arts, suggesting that they need to try out software before buying, or audition the music before committing to the $1 that it would take to actually buy it, and of course contribute their personal library to the internet. This rationalization of helping oneself to the free buffet is to be found on “warez” groups and file-sharing sites worldwide. While in a small number of cases this may come true, the numbers of sales and the massive degradation of the market show that the conversion of a pirate to an honest consumer is a rare event, indeed.

Who is Winning

The companies that succeed are by and large the ones with control over infrastructure, such as Internet Service Providers (ISP) companies or search engines like Google, services that are hard to steal due to their size and complexity. However, a big reason they succeed is that they turn a blind eye to the massive piracy going on. It falls on the owner of intellectual property to find infringers and prove ownership, rather than for the users to seek permission, and there are no consequences for serial offenders. At this point, the rate of theft is so high that a small business would have to spend all its resources “stamping out” fires, only to have them re-appear somewhere else.

Art without Commerce

Now that we have established that it is difficult if not impossible to make money on intellectual property, unless you can afford a fleet of lawyers, how can we, the artists make enough money to spend adequate time on doing our work? Is it even possible to be a professional in the arts anymore? Let’s look at some of the possibilities:

1. Make our prices so low that nobody will bother to steal our work. This would, of course mean we need more products to sell in order to make money on volume rather than quality. Stock music and photo sites have done just that, selling wares “by the pound” for low prices. This is about the only way anybody is selling much of anything. The downside: it will be necessary to “crank out” your work with minimal levels of creative effort; likewise new entries in the business won’t have the time to learn to do the work this fast. In either case, it’s hard to imagine this kind of sweatshop creation as a move forward.

2. Find independent financial backing. Going back to the days of art patrons, this avoids the pitfalls of supply-and-demand economics. Funding could come from a wealthy arts enthusiast, a large corporation, a foundation, or a government grant. Grant-writing has become a career field because of this pathway. To succeed here would suggest spending more time on PR and sales rather than on refining one’s craft.

3. Do it in your spare time: Going back to the initial premise, that real quality art requires massive time, training, practice and personal sacrifice, it seems difficult to imagine world-class work being done “on the side.” There are exceptions, however, such as composer Charles Ives, who wrote his music as a hobby, while running an insurance business.

4. Be independently wealthy. Not really a “choice,” but in the days of the British Empire, the Nobility, when not fox hunting and steeplechasing, were known for their intellectual and artistic pursuits. Of course, their abundant free time was created on the backs of a miserable under-class of workers living in poverty. This option isn’t really available to many, but it may be one of the only ways people will be able to slow down and do careful work.

5. Academia: Many people, especially those in less commercial fields, choose to just keep getting degree after degree, racking up astounding student debt. Within the cozy confines of their chosen school, they may achieve some version of fame and success amongst their peers, while insulated from the storms of the marketplace. We all know the “professional student,” with everybody asking “when are they going to finally finish school?” Once they do finish, they may be able to find a position as a teacher, and do their work within the same environment. This is probably one of the best situations, as long as there are enough students to keep the institution afloat. These days, it is difficult to make the case of the arts as a vocation, and recent federal rules about “gainful employment” will make this a less sustainable model, especially for smaller schools.

6. Niche Markets: There are areas people will spend money without too much complaint: As an example, some of my piano students are kids, and their parents are choosing to pay for music lessons simply as “character education” without any pretense of them becoming professional musicians. Likewise, my wife, a photographer, takes portraits of families and children, something people buy that can’t be found on the internet. So far, it isn’t possible to steal a stock photo of your own child. I also play piano at restaurants and hotels, where they feel a human musician is superior to a recording. (though this is less and less the case, and the prices are low)

Whither the Artist?

Will we see the end of careers in the arts? It certainly seems possible, since the time it takes to really “dig deep” is very difficult to justify. I certainly hope I am wrong.

Randy, another great article. Thank you. I agree with most of your reasoning, however I would like to say a few words based on my short-lived experience as a music and art enthusiast.

First of all, I believe that it is up to us, the individual artists, to STOP giving away our creations for free. This practice not only disincentives people from acquiring the content at a later time (if that ever even happens), but also implies and sends the message that our song, album or performance have no intrinsic value on the market, other than a intangible one. Solo acts and bands alike believe that exposure is what’s best and therefore make their music available on spotify, bandcamp, pandora, etc, in hopes that this will lead to future monetary gains that will come from music sales or live performances. Not true. This might work for a handful of people, but the vast majority will not see a dime from these efforts and the only beneficiaries are the companies that provide the service at the artist expense. What I believe we need to do when it comes to selling our music, is to create strong foundational niche markets. There are many people out there that truly care for music and want to support it financially (myself included) every way they can because we just simply understand and appreciate the the amount of effort and cost associated with any creative endeavor. As a professional Disc Jockey, I am constantly buying music in all formats, but specially on vinyl, when available. I go to as many live shows as I can, because I know that the best sounding record will never get close enough to the sound experience of a live performance. In my opinion, part of our “failure” resides, not in the fact that we are not good artists, but perhaps that we are terrible communicators when it comes to educating our audience. This in one hand, on the other hand, the reality is that in order to thrive financially, we must rely on versatility, which in our world can be translated to: playing live, working as studio musicians, as teachers, arrangers, composers, booking agents, etc,etc.

Artistry will never cease to exist, but in order for it to live a healthy life, it needs to be constantly evolving and adapting, just like everything else. As much as we work hard on the pursuit of becoming better musicians, we also need to become better story tellers of our craft, its relevance and the “real cost” of not feeding it properly.

WE are the industry and we should demand it works under our terms, not the other way around. As someone once said, “A doctor might save your life, but it is art what makes worth living”

Randy, my name’s Jeff and I took your studio performance classes as a drummer at AIM (before the second M). I’ve been a fan of your writing here, sometimes reflections or sometimes provocative pieces and anything in between. So many thoughts have run through my head after twice reading this post over two days. (If my response doesn’t format itself in this box sorry for the readability issues).

I graduated from AIM (fine…AIMM) and was fortunate enough to fall into a teaching gig that I’ve held for over six years. For my students who’re old enough – and talented enough, skilled enough and who have been afforded the 10,000+ hours of time which mastery takes, to parse out your accurate introduction’s factors – I feel privileged to give him/her and the parents the “Is this viable?” talk should the student show promise and interest in pursuing The Path. It’s not a pristine highway for the whole trip, with perfectly clear mile markers and rest stops

and attractions along the drive. It can be. Rarely, though. Maybe if you’ve met

the factors outlined in your post and have that good ol’ right-place-right-time

opportunity. Or sometimes before you get on the highway you have to traverse a couple dirty backroads then get lost and turn around, despite your Driver’s Ed classes, your license, and your years of experience behind your nice investment of an automobile. Metaphors abound. For those coming-of-agers I talk to, I emphasize the balance of concrete reality and positivity (Sure, gigs and sessions can be fun; a lot of our job is called playing, after all). At heart, the

conversation isn’t anything but a culmination of pointers from me passed down

from the greats, the history of the profession, and also directly from my

teachers at AIMMM.

Now, inherent in artists are usually feelings of borderline transcendent fulfillment through their art and the career they’re (trying to) make of it. Likewise, The Path instills in them integrity, a sustenance in its own right however lacking in its monetary measurement that quality is. These and more sentiments are usually fostered – almost practiced right along with their technique and facility on the instrument – during the youngsters’ upbringing. Certainly, it’s been tough to keep my own sentimental tank full on my metaphorical trip down the highway, and since your posting’s topic is one of earning money such “feels” have no room in the discussion. In their place, real and at times unabashedly pessimistic instructors stepped in to fortify my art by making it just as much an asset to the industry. Granted, I came into your and Tom Knight’s and Creig’s classes already appreciating and having cultivated that sterilized real-world mentality, nevertheless when I graduated I not only grew my chops to say what I the artist want to say on the instrument in any given style or situation, I also fulfilled that credential that pokes out most: I love playing what the bandleader asks of me. Playing what supports the song – regardless of my artistic interest I’m personally

pursuing on my own time – is what gives me ultimate meaning, purpose, and

fulfillment of expression (artistic payoffs?), and suddenly my hired gun, session

player situations become art in their own right. I excel as best I can at handling what the songwriter needs me to do and then I get the fuck out of the way. “An ego checked is a check cashed,” I believe was Tom Knight’s chiasmus. But to respect your argument, you’re indeed right that the check I get can be next

to nothing because of your reasons outlined. Thus your entire question (Will careers in the arts come to an end) has to be asked again, and the answer of “yes” becomes so threateningly apparent that it elevates the question to rhetorical

status.

An aside, perhaps, just perhaps, I might add to your post’s

factor list a fourth item, hardly able to be practiced, more of a byproduct or

something, nevertheless contributing to making “good” art the post’s outset

asks about, but only if the term ‘good’ can take on a meaning like ‘useful, profitable, able to be appreciated by the largest consumer audience

without sacrificing authentic craftsmanship and integrity on the part of its

creator.’

“Musicianship,” I guess? “Etiquette?” Maybe I won’t name the item

hoping to signify its great, un-teachable nature. Sadly though, the dismal

economics in art today will just as well signify its great, un-depositable nature at the ATM.